Inside the lab: research news from our partner CRG

[read the original article for EuroStemCell.org here]

[DISPLAY_ULTIMATE_SOCIAL_ICONS]Communicating scientific results from health related issues has always been an exciting task but it also has a never-know-how-much-to-explain component that can bring doubts and misleading concepts to public audiences. Members of the public are always keen to know how and when research results will be applied in human patients, a common question faced by basic research institutions like the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), in Barcelona.

Explaining that we devote endless working hours looking for, not a health treatment or a new drug development per se, but answers to questions about how nature works is a difficult task, especially in these days of economic uncertainty.

The CRG focuses on an integrated view of nature, from the genes inside a single cell to what is happening in an entire organism. We have four research programs: bioinformatics and genomics, cell and developmental biology, systems biology and (the largest program) gene regulation, stem cells and cancer. We are delighted to use this opportunity to tell you about the latest news on research in this last program.

The basic and applied science conundrum

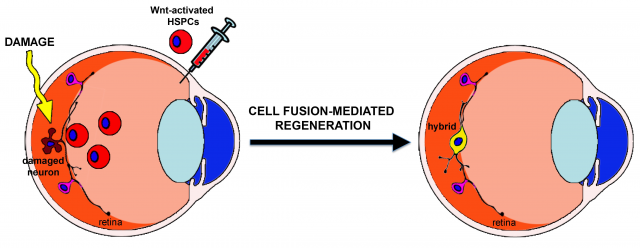

On 11th July, María Pía Cosma and members of her group “Reprogramming and Regeneration” at CRG published a paper (1) in the journal Cell Reports. In it, they explain how they succeeded in using a process called cell-cell fusion to reprogram neurons (nerve cells) in the retina and regenerate damaged tissue in mice:

Retinal damage (or retinopathy) is frequently a manifestation of diseases like sickle-cell anaemia, hypertension and diabetes among others. If the retina gets severely damaged, there isn’t an effective treatment and the damage cannot currently be repaired.

The retina is made up of layers of several different types of cells. Left: A piece of normal retinal tissue stained purple; Right: inside retinal tissue. From Sanges, et al, 2013, Cell Reports.

The retina is made up of layers of several different types of cells. Left: A piece of normal retinal tissue stained purple; Right: inside retinal tissue. From Sanges, et al, 2013, Cell Reports.

Cosma’s lab focuses on understanding in detail (right down to the molecules involved) exactly how cell reprogramming works and how it is controlled. In reprogramming, a specialized differentiated cell (like a skin cell) can be converted into a stem cell or another type of specialised cell (like a blood cell). Cosma’s group want to find out whether this process ” contributes effectively to tissue regeneration in higher vertebrates”. They pursue this goal by studying one particular reprogramming mechanism called “cell-cell fusion”, where different cells types are joined or fused together to “reprogram” the resulting cell.

This process of cell fusion also occurs spontaneously in the body in many developmental processes, “such as fertilization and muscle and bone development” and scientists have been studying it since the mid seventies. What Cosma’s lab has done is to distinguish the molecular pathway – the biological process or ‘route’ – by which the neurons in the retina do it.

Cosma’s lab’s findings have raised the hopes of people with retinal damage all over the world. But it is an important piece of a very complex puzzle. The press office of the CRG was very careful not to describe these findings as a miraculous cure, or a new cloning advance, or a breakthrough that will change people’s live. We did announce it correctly and precisely from our scientific point of view, that’s our job. But we must also give the public an indication of where to direct their questions and doubts. That’s why we encourage people interested in clinical trials to visit their national (or regional) contact points on this matter, or provide them with information from quality content providers like EuroStemCell or OptiStem.

In the end, communications involves not only the communicator but also those who are receiving information, so we should be prepared to answer the questions society asks us with quality information, without trespassing professional boundaries, and while being as clear and as honest as we can be. It’s in this way that we really have the opportunity to communicate science to the public and make an impact on their lives.

We’re losing a great player

Salvador Aznar-Benitah is the head of the Epithelial Homeostasis and Cancer group at the CRG. He studies how normal cells regulate or control themselves during healthy maintenance of our body’s tissues, but also how cells de-regulate and develop cancer.

The ICREA research professor has recently been awarded with the Metastasis Research Prize from the “Beug Foundation“. This award focuses on Aznar-Benitah’s interest in understanding how skin cells from a specific kind of cancer called squamous cell carcinoma can convert “into bone- or lung-like cells, cells from organs where this cancer usually metastasizes to”. The idea is to gain an in-depth understanding of how cancer cells can convert into other types of cells so that the tumour spreads into such different tissues.

Last year Aznar-Benitah was awarded an ERC Starting Grant for his work on how epidermal stem cells (the stem cells responsible for making new skin cells) are regulated by circadian rhythms. This happens to have a lot to do with normal tissue maintenance and aging, another subject studied by his peer at the CRG, Bill Keyes, that I suggest you read more about later. Next September Aznar-Benitah will leave the CRG for a new position at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB), also in Barcelona.

People usually ignore what scientists do in their labs from day to day. The media, and research centres too, have focused on communicating the findings and results of research, while leaving behind ideas about what we actually do in our work. I believe we should all work harder to share our research while we are doing it, to describe how we work as researchers and not to wait until the end of the long discovery process to tell people about our studies. There are a lot of things to write about how research is done and we should not rely solely on results and publications.

CRG also has a particular challenge for its communication efforts: We are a publicly funded, independent research centre focused on basic genome research and are outside the types of institutions commonly recognised for their role in research, such as universites, medical institutions or companies. This means CRG has a bigger burden to overcome to make our voices heard and make people aware that we exist. But we aren’t here because our jobs are easy, right?

Find out more:

- EuroStemCell fact sheet, The eye and stem cells: the path to treating blindness

- Beug Foundation press note about Metastasis Research Prize

- Scientific research papers (journal subscriptions may be required):

- 1- Sanges D, Romo N, Simonte G, Di Vicino U, Diaz Tahoces A, Fernández E and Cosma MP. “Wnt/β-Catenin Signalling Triggers Neuron Reprogramming and Regeneration in the Mouse Retina” Cell Reports. July 11, 2013.

- Sullivan and Eggan, 2006 Sullivan, S., and Eggan, K. (2006). The potential of cell fusion for human therapy. Stem Cell Rev. 2, 341–349

- Miller RA, Ruddle FH. Pluripotent teratocarcinomathymus somatic cell hybrids. Cell 1976; 9:45–55.

- The information about Salvador’s award was taken from the original press note at the Beug Foundation: http://www.beugstiftung-metastase.org/?q=node/88

Special acknowledgments to Emma Kemp, from Eurostemcell.org for her style and english improvements on the text.